Introducing Monoio: a high-performance Rust Runtime based on io-uring

Projects:

Overview

Although Tokio is currently the ‘de facto’ standard for Rust asynchronous runtime, there is still some distance to go to achieve the ultimate performance of network middleware. In pursuit of this goal, the CloudWeGo Rust Team has explored providing asynchronous support for Rust based on io-uring and developed a universal gateway on this basis.

This blog includes the following content:

- Introduction to Rust asynchronous runtime;

- Design essentials of Monoio;

- Comparison and selection of runtime and application.

Rust Asynchronous Mechanism

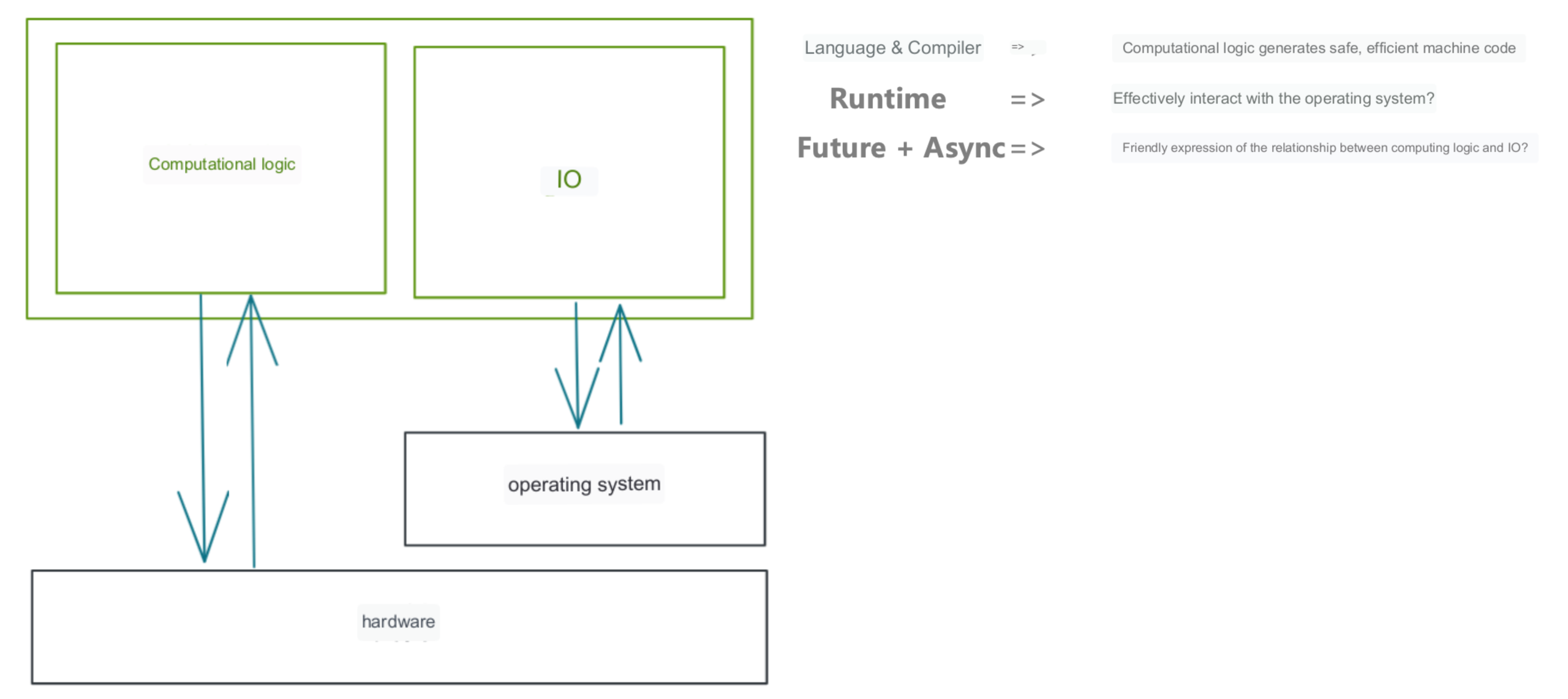

With the help of Rustc and LLVM, Rust can generate machine code that is efficient and secure enough. However, besides computing logic, an application often involves I/O, especially for network middleware, where I/O takes up a considerable proportion.

I/O operations require interaction with the operating system, and writing asynchronous programs is usually not a simple task. How does Rust solve these two problems? For example, in C++, it is common to write callbacks, but we don’t want to do this in Rust because it may encounter many lifetimes related issues.

Rust allows the implementation of a custom runtime to schedule tasks and execute syscalls, and provides unified interfaces such as Future. In addition, Rust provides built-in async-await syntax sugar to liberate programmers from callback programming.

Example

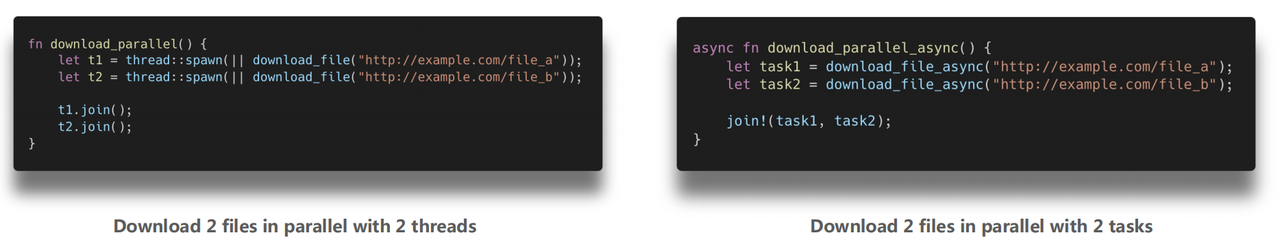

Let’s start with a simple example to see how this system works. When downloading two files in parallel, you can start two threads in any language to download each file and then wait for the threads to finish execution. However, we don’t want to start unnecessary threads just to wait for IO. If we need to wait for IO, we want the threads to do something else and only perform the IO operation when it’s ready.

This event-driven triggering mechanism is often encountered in C++ in the form of callbacks. Callbacks interrupt our sequential logic, making the code less readable. Additionally, it’s easy to encounter issues with the lifecycle of variables that callbacks depend on, such as releasing a variable referenced by a callback before the callback is executed.

However, in Rust, you only need to create two tasks and wait for them to finish execution.

In comparison to threads, asynchronous tasks are much more efficient in this example, but they don’t significantly complicate the programming.

In the second example, let’s mock an asynchronous function called do_http that directly returns 1. In reality, it could involve a series of asynchronous remote requests.

On top of that, we want to combine these asynchronous functions. Let’s assume we make two requests and add up the results, and finally add 1. This is the sum function in this example.

Using the async and await syntax, we can easily nest these asynchronous functions.

#[inline(never)]

async fn do_http() -> i32 {

// do http request in async way

1

}

pub async fn sum() -> i32 {

do_http().await + do_http().await +1

}

This process is very similar to writing synchronous functions, which means it’s more procedural programming rather than state-oriented programming. By using this mechanism, we can avoid the problem of writing a bunch of callbacks, bringing great convenience to programming.

The Secret Behind Async/Await

Through these two examples, we can see how async is used in Rust and how convenient it is to write code with it. But what is the underlying principle behind it?

#[inline(never)]

async fn do_http( ) -> i32 {

// do http request in async way

1

}

pub async fn sum() -> i32 {

do_http().await + do_http().await + 1

}

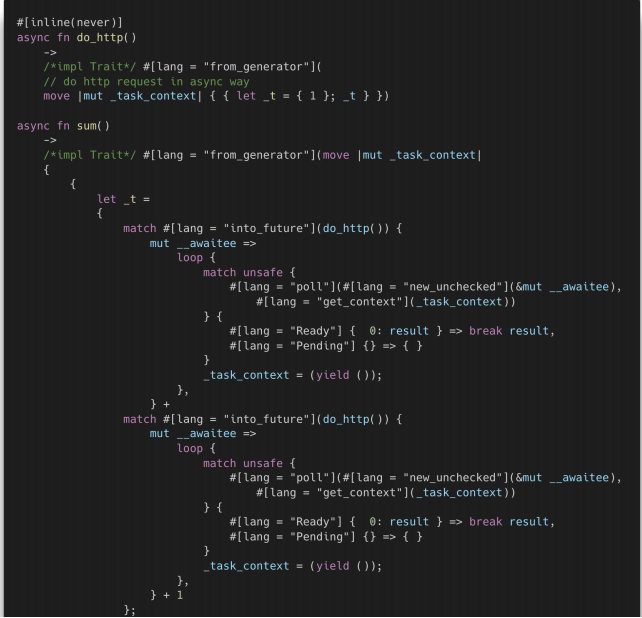

The examples we just saw were written using Async and Await, which ultimately generates a structure that implements the Future trait.

Async and Await is actually syntactic sugar that can be expanded into Generator syntax at the HIR (High-level Intermediate Representation) stage. The Generator syntax is then further expanded by the compiler into a state machine at the MIR (Mid-level Intermediate Representation) stage.

Future Abstraction

The Future trait is defined in the standard library. Its interface is very simple, consisting of only one associated type and one poll method.

pub trait Future {

type Output;

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output>;

}

pub enum Poll<T> {

Ready(T),

Pending,

}

The Future describes the interface exposed by the state machine:

- Driving the state machine execution: The Poll method, as the name suggests, drives the execution of the state machine. Given a task, it triggers the task to perform state transitions.

- Returning the execution result:

- When encountering a blocking operation: Pending

- When execution is completed: Ready + return value

From this, we can see that the essence of an asynchronous task is to implement the state machine of a Future. The program can manipulate it using the Poll method, which may indicate that it’s currently encountering a blocking operation or that the task has completed and returned a result.

Since we have the Future trait, we can manually implement it. In doing so, the resulting code can be more readable compared to expanding with the Async and Await syntactic sugar. Below is an example of manually generating a state machine. If we were to write it using the Async syntax, it might be as simple as an async function returning a 1. However, when manually writing it, we need to define a custom struct and implement the Future trait for that struct.

// auto generate

async fn do_http() -> i32 {

// do http request in async way

1

}

// manually impl

fn do_http() -> DOHTTPFuture { DoHTTPFuture }

struct DoHTTPFuture;

impl Future for DoHTTPFuture {

type Output = i32;

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, _cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output>{

Poll::Ready(1)

}

}

The essence of an async function is to return an anonymous structure that implements the Future trait. This type is automatically generated by the compiler,

so its name is not exposed to us. On the other hand, when manually implementing it, we define a struct called DoHTTPFuture and implement the Future trait for it.

Its output type, just like the return value of an async function, is an i32. These two approaches are equivalent.

Since we only need to immediately return the number 1 in this case without any waiting involved, we can simply return Ready(1) in the poll implementation.

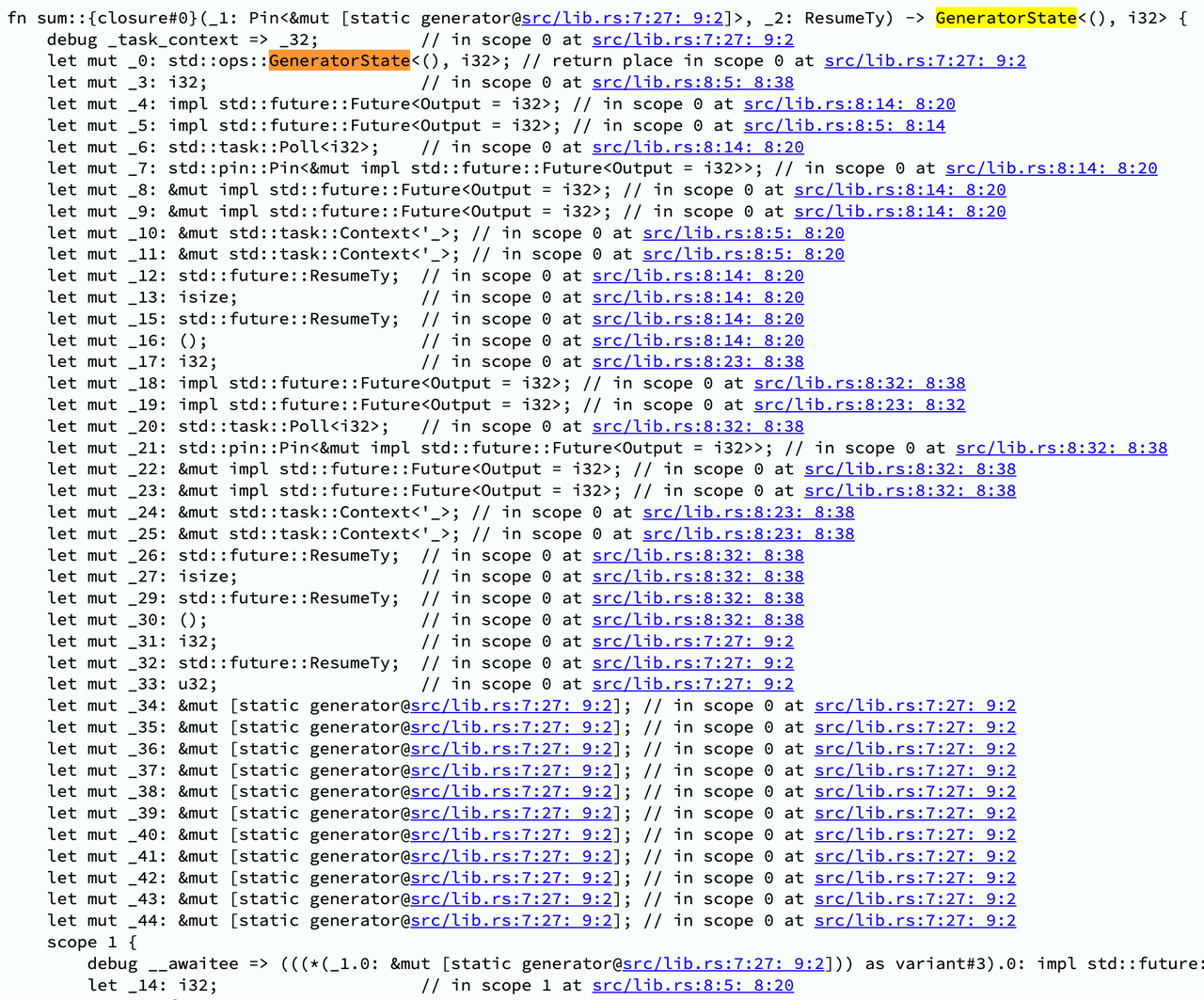

In the previous example of sum, it involved the composition of asynchronous logic: making two calls to do_http and then adding the two results together.

If we were to manually implement this, it would be slightly more complex because it would involve two await points. Once await is involved, it essentially becomes a state machine.

Why a state machine? Because each await point may potentially block, and the thread cannot stop and wait there. It must switch to execute other tasks.

In order to resume the previous task later, its corresponding state must be stored. Here, we define two states: FirstDoHTTP and SecondDoHTTP.

When implementing the poll function, we enter a loop where we match the current state and perform state transitions accordingly.

// auto generate

async fn sum( ) -> i32 {

do_http( ).await + do http( ).await + 1

}

// manually impl

fn sum() -> SumFuture { SumFuture::FirstDoHTTP(DoHTTPFuture) }

enum SumFuture {

FirstDoHTTP(DOHTTPFuture),

SecondDoHTTP( DOHTTPFuture, i32),

}

impl Future for SumFuture {

type Output = i32;

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<' >) -> Poll<Self::Output> {

let this = self.get mut( );

loop {

match this {

SumFuture::FirstDoHTTP(f) => {

let pinned = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(f) };

match pinned.poll(cx) {

Poll::Ready(r) => {

*this = SumFuture::SecondDoHTTP(DOHTTPFuture,r);

}

Poll::Pending => {

return Pol::Pending;

}

}

}

SumFuture::SecondDoHTTP(f, prev_sum) => {

let pinned = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(f) };

return match pinned.poll( cx) {

Poll::Ready(r) => Poll::Ready(*prev_sum + r + 1),

Poll::Pending => Pol::Pending,

};

}

}

}

}

}

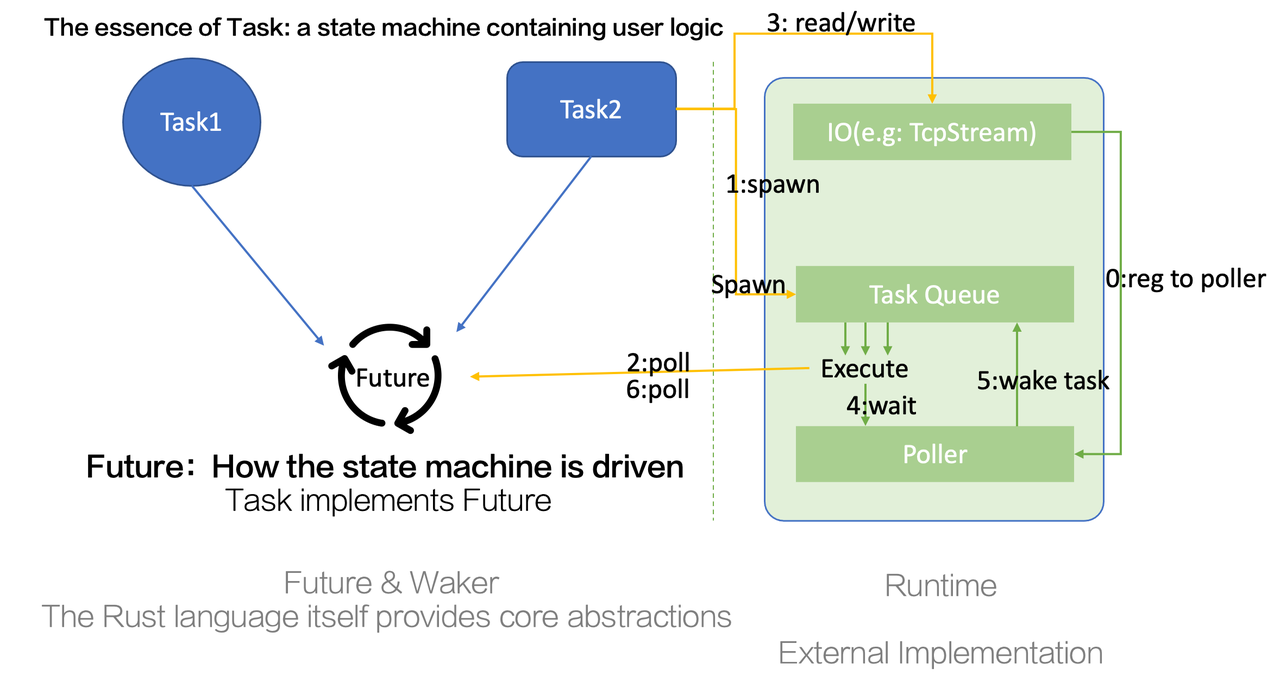

The Relationship between Task, Future and Runtime

Let’s use the example of TcpStream’s Read/Write to illustrate the entire mechanism and the relationship between components.

First, when we create a TCP stream, the component internally registers it with a poller. This poller can be thought of as a wrapper for epoll (the specific driver used depends on the platform).

Now, let’s go through the steps in order. We have a task that needs to be spawned for execution. Essentially, spawning a task means putting it into the task queue of the runtime. The runtime will continuously take tasks from the task queue and execute them. Execution involves advancing the state machine, which means invoking the poll method of the task. This brings us to the second step.

We execute the poll method, which is essentially implemented by the user. Within this task, the user will invoke TcpStream’s read/write functions. Internally, these functions eventually make system calls to perform their functionality. However, before executing the syscall, certain conditions must be met, such as the file descriptor (fd) being ready for reading or writing. If it doesn’t meet these conditions, even if we execute the syscall, we will only receive a WOULD_BLOCK error, resulting in wasted performance. Initially, we assume that newly added fds are both readable and writable, so the first poll will execute the syscall. If there is no data to read or the kernel’s write buffer is full, the syscall will return a WOULD_BLOCK error. Upon detecting this error, we modify the readiness record and set the relevant read/write for that fd as not ready. At this point, we can only return Pending.

Next, we move to the fourth step. When all the tasks in our task queue have finished execution and all tasks are blocked on I/O, it means that none of the I/O operations are ready. The thread will continuously block in the poller’s wait method, which can be thought of as something similar to epoll_wait. When using io_uring for implementation, this may correspond to another syscall.

At this point, entering a syscall is reasonable because there are no tasks to execute, and there is no need to continuously poll the I/O status. Entering a syscall allows the CPU time slice to be yielded to other tasks on the same machine. If any I/O operation becomes ready, we will return from the syscall, and the kernel will inform us which events on which fds have become ready. For example, if we are interested in the readability of a specific fd, it will inform us that the fd is ready for reading.

We need to mark the readiness of the fd as readable and wake up the tasks waiting on it. In the previous step, there was a task waiting here, dependent on the I/O being readable. Now that the condition is met, we need to reschedule it. Waking up essentially means putting the task back into the task queue. Implementation-wise, this is achieved through the wake-related methods of a Waker. The handling behavior of wake is implemented by the runtime, and the simplest implementation is to use a deque to store tasks, pushing them in when waking. More complex implementations may consider mechanisms such as task stealing and distribution for cross-thread scheduling.

When this task is polled again, it will perform TcpStream read internally. It will find that the I/O is in a readable state, so it will execute the read syscall, and at this point, the syscall will execute correctly, and TcpStream read will return Ready to the outside.

Waker

Earlier, we mentioned the Waker. Now let’s discuss how the Waker works. We know that a Future is essentially a state machine, and each time it is polled, it returns Pending or Ready. When it encounters an IO block and returns Pending, who detects the IO readiness? And how is the Future driven again once the IO is ready?

pub trait Future {

type Output;

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output>;

}

pub struct Context<'a> {

//obtain the Waker used to wake up the Task.

waker: & a Waker,

//mark field, can be ignored

_marker: PhantomData<fn(&'a ()) -> &'a ()>,

}

Inside the Future trait, in addition to containing the mutable borrow of its own state machine, there is another important component called Context. Currently, the Context only has one meaningful member, which is the Waker. For now, we can consider the Waker as a trait object constructed and implemented by the runtime. Its implementation effect is that when we wake this Waker, the task is added back to the task queue and may be executed immediately or later.

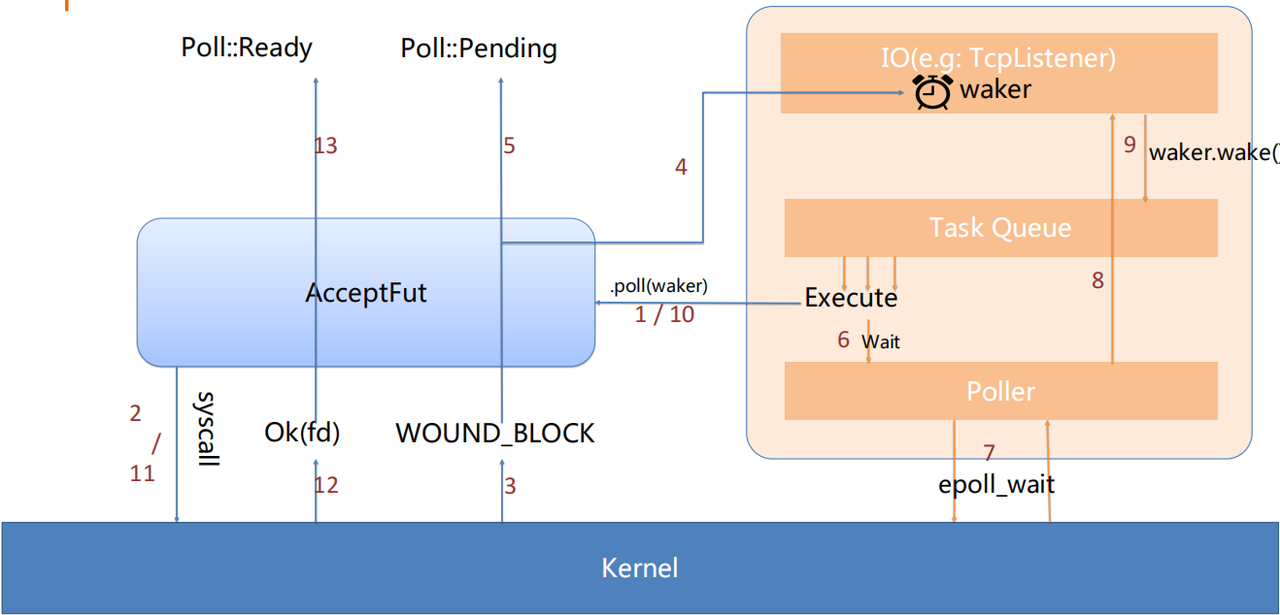

Let’s take another example to understand the whole process:

When a user calls listener.accept() to generate an AcceptFut and waits:

- The

fut.awaitinternally calls thepollmethod of the Future using thecx(Context). - Inside the

poll, a syscall is executed. - There are no incoming connections, so the kernel returns

WOULD_BLOCK. - The Waker in the

cxis cloned and stored in the associated structure ofTcpListener. - The current poll returns Pending to the outside.

- The Runtime has no tasks to execute, so the control is transferred to the Poller.

- The Poller executes

epoll_waitand enters a syscall to wait for IO readiness. - It searches for and marks all ready IO states.

- If there is an associated Waker, it wakes and clears it.

- The task waiting for accept is added back to the execution queue and is polled again.

- Another syscall is executed.

- 12/13, Kernel returns the syscall result, and poll returns Ready.

Runtime

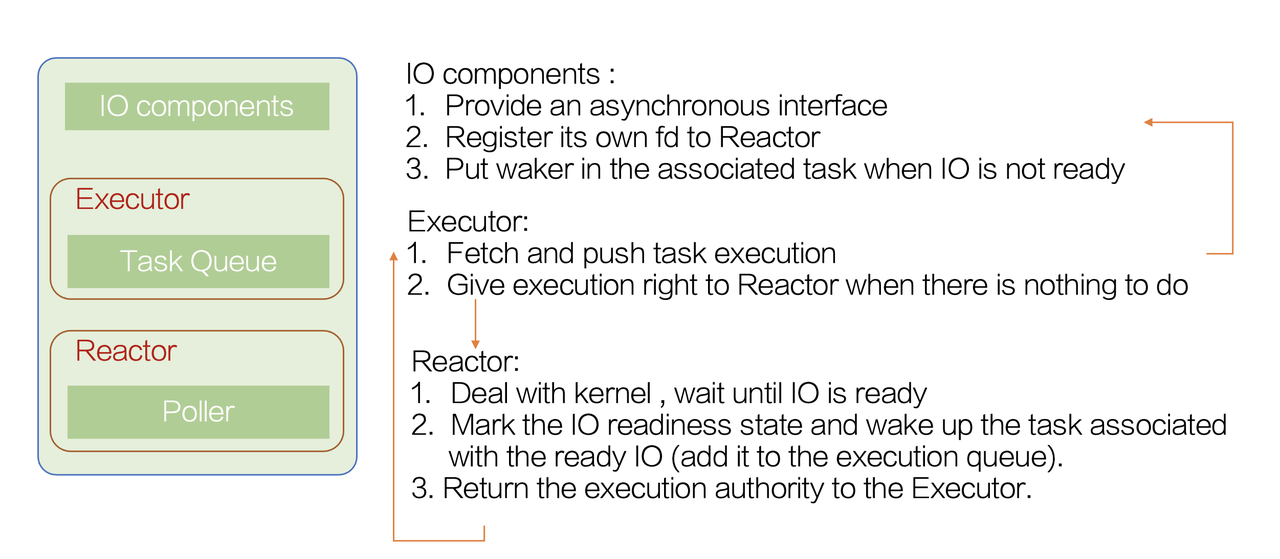

- Let’s start with the executor. It has an executor and a task queue. Its job is to continuously take tasks from the queue and drive their execution. When all tasks have completed and it must wait, it hands over control to the Reactor.

- Once the Reactor receives control, it interacts with the kernel and waits for IO readiness. After IO is ready, we need to mark the readiness state of that IO and wake up the tasks associated with it. After waking up, the control is handed back to the executor. When the executor executes the task, it will invoke the capabilities provided by the IO component.

- The IO component needs to provide these asynchronous interfaces. For example, when a user wants to use TcpStream, they need to use a TcpStream provided by the runtime instead of the standard library directly. Secondly, the component should be able to register its file descriptor (fd) with the Reactor. Thirdly, when the IO is not ready, we can place the waker associated with that task in the relevant area.

That’s roughly how the asynchronous mechanism in Rust works.

Monoio Design

Monoio is a thread-per-core Rust runtime with io_uring/epoll/kqueue. And it is designed to be the most efficient and performant thread-per-core Rust runtime with good platform compatibility.

The following will describe the key points of the Monoio Runtime design in four parts:

- Async IO interface based on GAT (Generic Associated Types).

- Driver detection and switching transparent to the upper layer.

- Balancing performance and functionality.

- Providing compatibility with the Tokio interface.

Pure async IO interface based on GAT

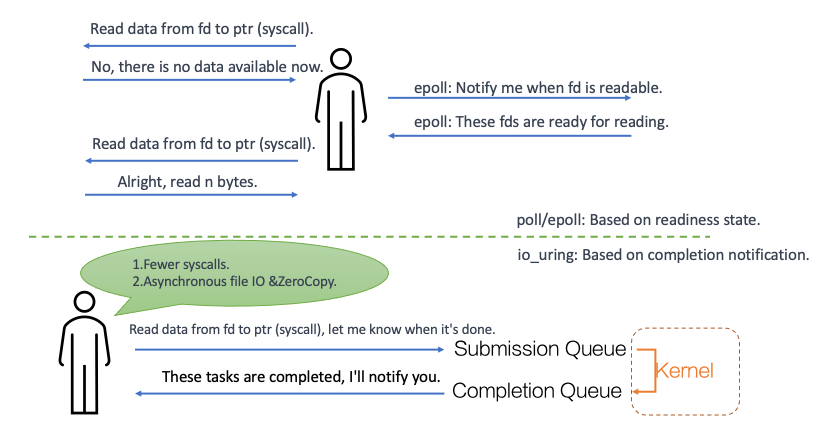

First, let’s introduce two notification mechanisms. The first one is similar to epoll, which is a notification based on readiness states. The second one is the io-uring mode, which is a “completion notification” based mode.

In the readiness-based mode, tasks wait and detect IO readiness through epoll, and only perform syscalls when the IO is ready. However, in the completion notification-based mode, Monoio can be lazier: it simply tells the kernel what the current task wants to do and then lets go.

io_uring allows users and the kernel to share two lock-free queues: the submission queue (SQ) is written by user-space programs and consumed by the kernel, while the completion queue (CQ) is written by the kernel and consumed by user-space. The enter syscall can be used to submit the SQEs (Submission Queue Entries) in the queue to the kernel, and optionally, it can also enter and wait for CQEs (Completion Queue Entries).

In syscall-intensive applications, using io_uring can significantly reduce the number of context switches, and io_uring itself can also reduce data copying in the kernel.

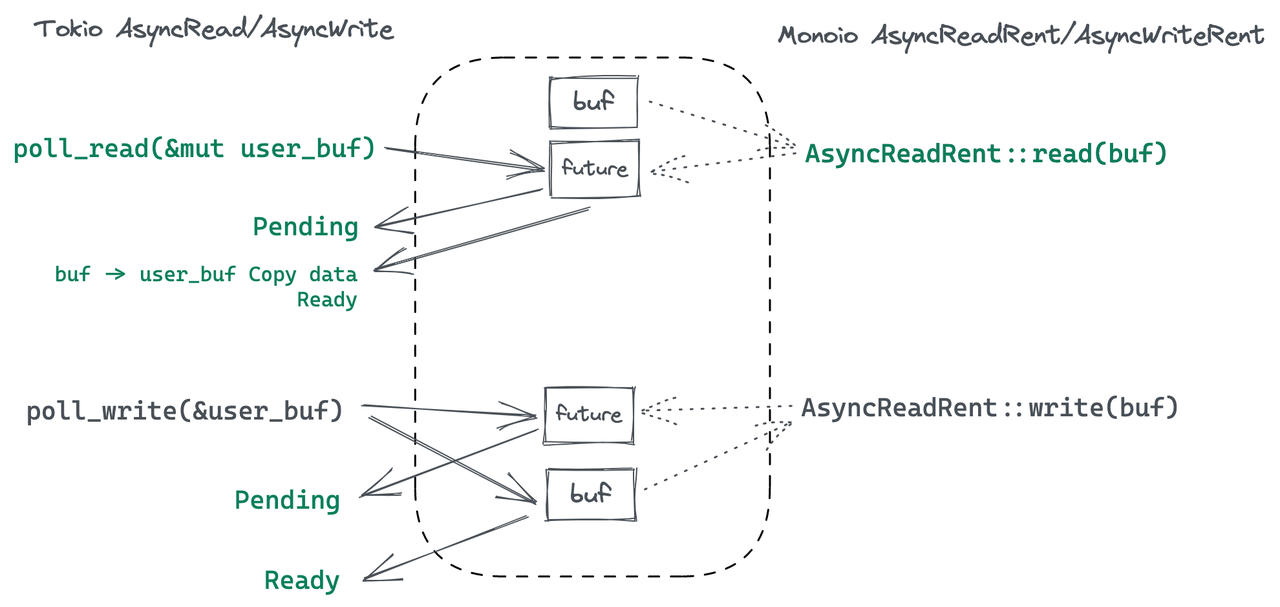

The differences between these two modes will greatly influence the design of the Runtime and IO interface. In the first mode, there is no need to hold the buffer while waiting;

the buffer is only needed when executing the syscall. Therefore, in this mode, users can pass the &mut Buffer when calling the actual poll (e.g., poll_read).

In the second mode, once submitted to the kernel, the kernel can access the buffer at any time, and Monoio must ensure the validity of the buffer before the corresponding CQE for that task returns.

If existing async IO traits (such as Tokio/async-std, etc.) are used, passing a reference to the buffer during read/write may result in memory safety issues such as Use-After-Free (UAF).

For example, if the user pushes the buffer pointer into the uring SQ when calling read, but immediately drops the created Future (read(&mut buffer)) and drops the buffer,

this behavior does not violate Rust’s borrowing rules, but the kernel will still access freed memory, potentially stomping on memory blocks allocated by the user program later on.

One solution in this case is to capture ownership of the buffer. When generating the Future, the ownership is given to the Runtime, so the user cannot access the buffer in any way, thus ensuring the validity of the pointer before the kernel returns the CQE. This solution is inspired by the approach used in Tokio-uring.

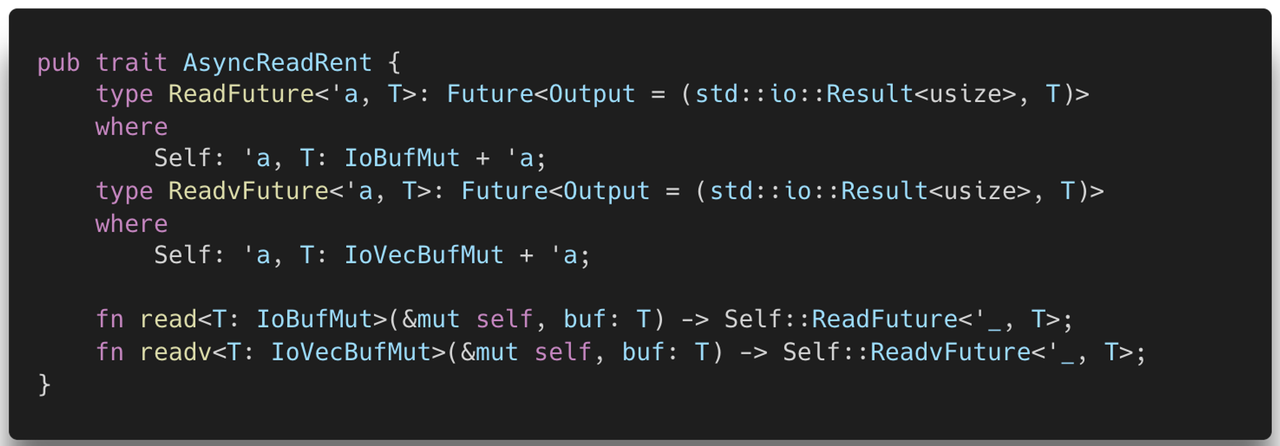

Monoio defines the AsyncReadRent trait. The term “Rent” refers to borrowing, where the Runtime takes the buffer from the user first and returns it later.

The type ReadFuture here has a lifetime generic, which is made possible by GAT (Generic Associated Types). GAT is now stable and can be used in the stable version.

When implementing the associated Future, the TAIT trait can be used directly with the async/await syntax, which is much more convenient and user-friendly compared to manually defining Futures.

This feature is not yet stable (it is now called impl trait in assoc type).

However, transferring ownership introduces new issues. In the readiness-based mode, canceling IO only requires dropping the Future. Here, if the Future is dropped,

it may lead to data flow errors on the connection (as the Future might be dropped at the moment when the syscall has already succeeded).

Additionally, a more serious problem is that the buffer captured by the Future will definitely be lost. To address these two issues, Monoio supports IO traits with cancellation capabilities.

When canceled, a CancelOp is pushed, and the user needs to continue waiting for the original Future to complete (as it has been canceled, it is expected to return within a short time).

The corresponding syscall may succeed or fail and return the buffer.

Automatic Driver Detection and Switching for Higher Level

The second feature is automatic driver detection and switching for high level components.

trait OpAble {

fn uring_op(&mut self) -> io_uring::squeue::Entry;

fn legacy_interest(&self) -> Option<(ready::Diirection, usize)>;

fn legacy_call(&mut self) -> io::Result<u32>;

}

- Specify the driver through features or code, and conditionally perform runtime detection.

- Expose a unified IO interface, namely AsyncReadRent and AsyncWriteRent.

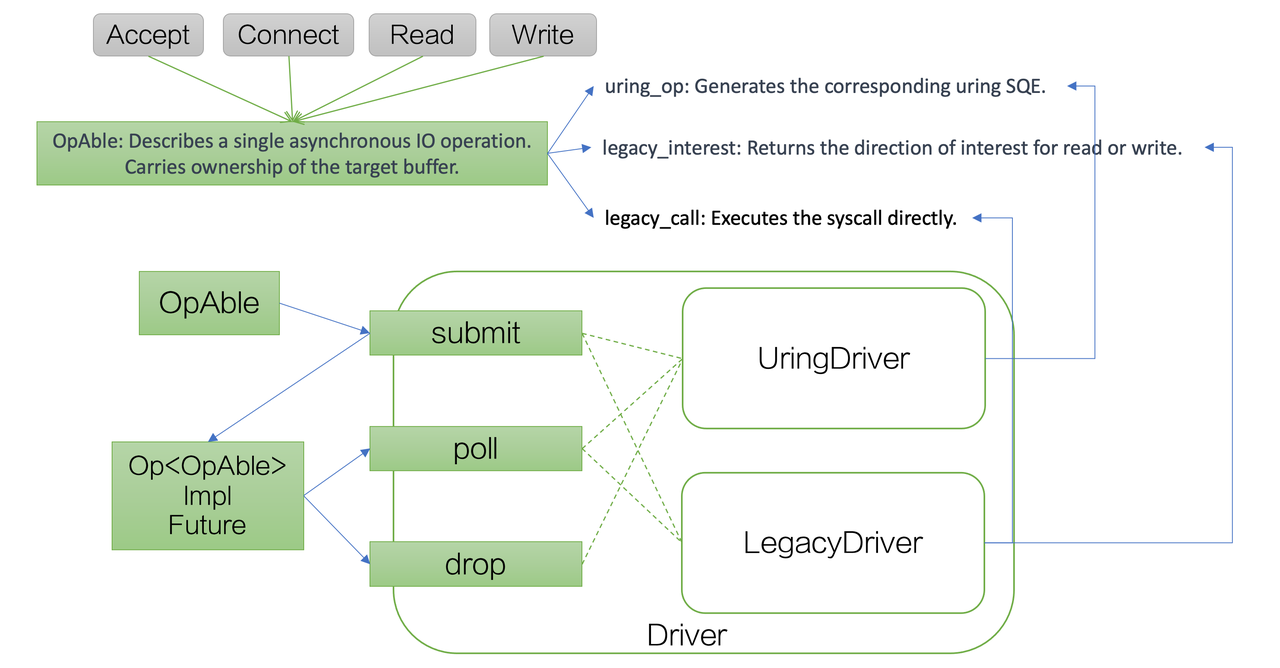

- Implement internally using the OpAble unified component (abstracting Read, Write, and other operations).

Specifically, for operations such as accept, connect, read, write, etc., which are implemented as OpAble, they correspond to the following three functions:

- uring_op: Generates the corresponding uring SQE.

- legacy_interest: Returns the direction of read/write it is interested in.

- legacy_call: Executes the syscall directly.

The entire process will submit a structure that implements OpAble to the driver. It will then return something that implements the Future. When polling or dropping, it will specifically dispatch to one of the two driver implementations, using one or two of the three functions mentioned.

Performance

Performance is the starting point and the major advantage of Monoio. In addition to the improvements brought by io_uring, it is designed as a thread-per-core Runtime.

- All tasks run only on fixed threads, without task stealing.

- The task queue is a thread-local structure, operated without locks or contention.

High performance stems from two aspects:

- High performance within the Runtime: Essentially equivalent to direct syscall integration.

- High performance in user code: Structures are designed to be thread-local and avoid crossing thread boundaries as much as possible.

Comparison of task stealing and thread-per-core mechanisms:

In the case of using Tokio, there may be very few tasks on one thread, while another thread has a high workload. In this situation, the idle thread can steal tasks from the busy thread, which is similar to how it works in Go. This mechanism allows for better utilization of the CPU and can achieve good performance in general scenarios.

However, cross-thread operations themselves incur overhead, and when multiple threads operate on data structures, locks or lock-free structures are required. Lock-free does not mean there is no additional overhead. Compared to purely thread-local operations, cross-thread lock-free structures can impact cache performance, and CAS (Compare and Swap) operations may involve some unnecessary loops. Moreover, this threading model also affects user code.

For example, suppose we need an SDK internally to collect some metrics from this program and aggregate them before reporting. Achieving optimal performance can be challenging with a Tokio-based implementation. However, with a thread-per-core Runtime structure, we can place the aggregated map in thread-local storage without any locks or contention issues. Each thread can start a task that periodically clears and reports the data in the thread-local storage. In scenarios where tasks may cross thread boundaries, we would need to use a global structure to aggregate the metrics and have a global task for reporting data. It becomes challenging to use lock-free data structures for aggregation in such scenarios.

Therefore, both threading models have their advantages. The thread-per-core model achieves better performance for tasks that can be processed independently. Sharing fewer resources leads to better performance. However, the drawback of the thread-per-core model is that it cannot fully utilize the CPU when the workload is unevenly distributed among tasks. For specific scenarios such as gateway proxies, the thread-per-core model is more likely to fully utilize hardware performance and achieve good horizontal scalability. Popular solutions like Nginx and Envoy employ this threading model.

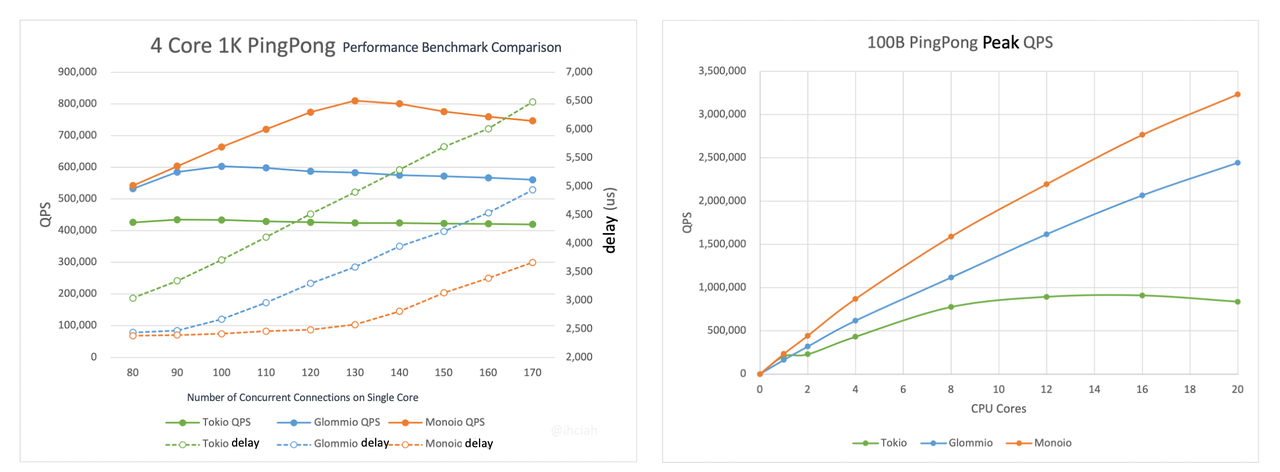

We have conducted some benchmarks, and Monoio demonstrates excellent performance scalability. As the number of CPU cores increases, you only need to add the corresponding threads.

Functionality

Thread-per-core does not imply the absence of cross-thread capabilities. Users can still use some shared structures across threads, which are unrelated to the Runtime. The Runtime provides the ability to wait across threads.

Tasks are executed within the local thread but can wait for tasks on other threads. This is an essential capability. For example, if a user needs to fetch remote configurations with a single thread and distribute them to all threads, they can easily implement this functionality based on this capability.

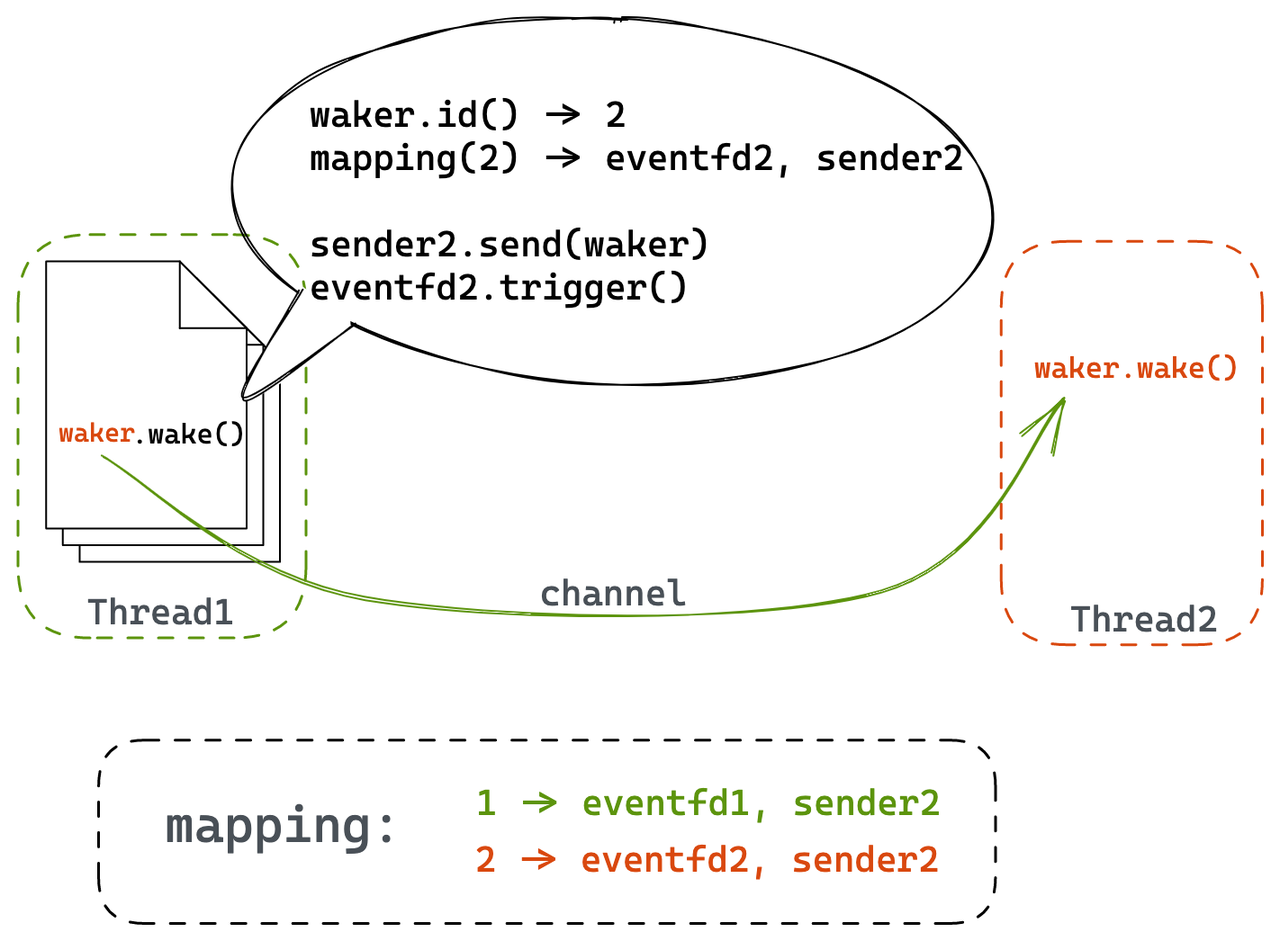

The essence of cross-thread waiting is for a task on another thread to wake up the local thread. In the implementation, we mark the ownership of tasks in the Waker. If the current thread is not the task’s owner thread, the Runtime will send the task to its owner thread using a lock-free queue. If the target thread is in a sleep state (e.g., waiting for IO in a syscall), the Runtime will wake it up using a pre-installed eventfd. After being awakened, the target thread will process the cross-thread waker queue.

In addition to providing the ability for cross-thread waiting, Monoio also offers the spawn_blocking capability for users to execute heavy computational logic without affecting other tasks in the same thread.

Compatibility Interfaces

Since many components (such as Hyper) are bound to Tokio’s IO traits, and as mentioned earlier, it is not possible to unify these two IO traits due to the underlying drivers. This can create difficulties in terms of ecosystem compatibility. For some non-hot-path components, it is necessary to allow users to use them in a compatible manner, even if it incurs some performance cost.

// tokio way

let tcp = tokio::net::TcpStream: connect("1.1.1.1.1:80").await.unwrap();

// monoio way(with monoio-compat)

let tcp = monoio_compat::StreamWrapper::new(monoio_tcp);

let monoio_tcp = monoio::net::TcpStream::connect("1.1.1.1:80").await.unwrap();

// both of them implements tokio:: io::AsyncReadd and tokio:: io: AsyncWrite

We provide a wrapper that includes a buffer, and when users use it, they need to incur an additional memory copy overhead. Through this approach, we can wrap components of Monoio into Tokio-compatible interfaces, allowing them to be used with compatible components.

Runtime Comparison & Applications

This section discusses some runtime comparison options and their applications.

We have already mentioned the comparison between uniform scheduling and thread-per-core. Now let’s focus on their application scenarios. For a large number of lightweight tasks, the thread-per-core mode is suitable. This is particularly applicable to applications such as proxies, gateways, and file IO-intensive tasks, making Monoio an excellent choice.

Additionally, while Tokio aims to be a general cross-platform solution, Monoio was designed from the beginning with a focus on achieving optimal performance, primarily using io_uring. Although it can also support epoll and kqueue, they serve as fallback options. For example, kqueue is primarily included to facilitate development on macOS, but it is not intended for actual production use (support for Windows is planned in the future).

In terms of ecosystem, Tokio has a comprehensive ecosystem, while Monoio lags behind in this aspect. Even with the compatibility layer, there are inherent costs. Tokio’s task stealing can perform well in many scenarios, but it has limited scalability. On the other hand, Monoio demonstrates good scalability, but it has certain limitations in terms of business scenarios and programming models. Therefore, Monoio is well-suited for scenarios such as proxies, gateways, and data aggregation in caches. It is also suitable for components that perform file IO, as io_uring excels in handling file IO. Without io_uring, there is no true asynchronous file IO available in Linux; only with io_uring can this be achieved. Monoio is also suitable for components that heavily rely on file IO, such as database-related components.

| Tokio | Monoio | |

|---|---|---|

| Scene | General, task stealing | Specific, thread-per-core |

| Platform | Cross-platform, epoll/kqueue/iocp | Specific, io_uring, epoll/kqueue as fallback |

| Ecosystem | comprehensive | Relatively lacking |

| Horizontal extensibility | Not Good Enough | Good |

| Application | General business | Proxy, Gateway, cache, data aggregate, etc |

Tokio-uring is actually a layer built on top of Tokio, somewhat like a distribution layer. Its design is elegant, and we have also referenced many of its designs, such as the ownership transfer mechanism. However, it is still based on Tokio and runs uring on top of epoll, without achieving full transparency for users. When implementing components, one can only choose between using epoll or using uring. If uring is chosen, the resulting binary cannot run on older versions of Linux. On the other hand, Monoio addresses this issue well and supports dynamic detection of uring availability.

Applications of Monoio

- Monoio Gateway: A gateway service based on the Monoio ecosystem. In optimized version benchmarks, its performance surpasses that of Nginx.

- Volo: An RPC framework open-sourced by the CloudWeGo team, currently being integrated. The PoC version demonstrates a 26% performance improvement compared to the Tokio-based version. We have also conducted some internal business trials, and in the future, we will focus on improving compatibility and component development to make Monoio even more user-friendly.