Introducing Shmipc: A High Performance Inter-process Communication Library

Projects:

We are excited to introduce an open source project - Shmipc, a high performance inter-process communication library developed by ByteDance. It is built on Linux’s shared memory technology and uses unix or tcp connection to do process synchronization and finally implements zero copy communication across inter-processes. In IO-intensive or large-package scenarios, it has better performance.

There isn’t much information on this area, so the open-source of Shmipc would like to contribute by providing a valuable reference. In this blog, we would like to cover some of the main design ideas of Shmipc, the problems encountered during the adoption process and the subsequent evolution plan.

- Design: https://github.com/cloudwego/shmipc-spec

- Implementation in Golang: https://github.com/cloudwego/shmipc-go

Background and Motivation

At ByteDance, Service Mesh has undergone a lot of performance optimization during its adoption and evolution. The traffic interception of Service Mesh is achieved by inter-process communication between the mesh proxy and the microservice framework’s agreed-upon addresses, which performs better than iptables solutions. However, conventional optimization methods no longer bring significant performance improvements. Therefore, we shifted our focus to inter-process communication, and Shmipc was born.

Design Ideas

Zero Copy

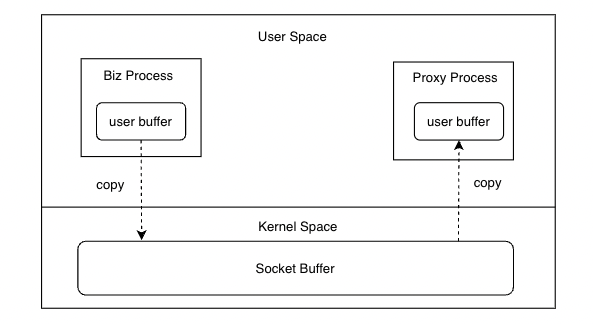

The two most widely used inter-process communication methods in production environments are unix domain sockets and TCP loopback (localhost:$PORT), and their performance differences are not significant from the benchmark. From a technical standpoint, both require copying communication data between user space and kernel space. In the RPC scenario, there are four memory copies in inter-process communication during a single RPC process, with two copies in the request path and two copies in the response path.

Although sequential copying on modern CPUs is very fast, eliminating up to four memory copies can still save CPU usage in large packet scenarios. With the zero-copy feature based on shared memory communication, we can easily achieve this. However, to achieve zero-copy, there will be many additional tasks surrounding shared memory itself, such as:

- In-depth serialization and deserialization of microservice frameworks. We hope that when a Request or Response is serialized, the corresponding binary data is already in shared memory, rather than being serialized to a non-shared memory buffer and then copied to a shared memory buffer.

- Implementing a process synchronization mechanism. When one process writes data to shared memory, another process does not know about it, so a synchronization mechanism is needed for notification.

- Efficient memory allocation and recycling. Ensuring that the allocation and recycling mechanism of shared memory across processes has a low overhead to avoid masking the benefits of zero-copy features.

Synchronization Mechanism

Consider different scenarios:

- On-demand real-time synchronization. Suitable for online scenarios that are extremely sensitive to latency. Notify the other process after each write operation is completed. There are many options to choose from on Linux, such as TCP loopback, unix domain sockets, event fd, etc. Event fd has slightly better benchmark performance, but passing fd across processes introduces too much complexity. The performance improvement it brings is not very significant in IPC, and the trade-off between complexity and performance needs to be carefully considered. At ByteDance, we chose unix domain sockets for process synchronization.

- Periodic synchronization. Suitable for offline scenarios that are not sensitive to latency. Access the custom flag in shared memory through high-interval sleep to determine whether there is data written. However, note that sleep itself also requires a system call and has greater overhead than reading and writing with unix domain sockets.

- Polling synchronization. Suitable for scenarios where latency is very sensitive but the CPU is not as sensitive. You can complete it by polling the custom flag in shared memory on a single core.

Overall, on-demand real-time synchronization and periodic synchronization require system calls to complete, while polling synchronization does not require system calls but requires running a CPU core at full capacity under normal circumstances.

Batching IO Operations

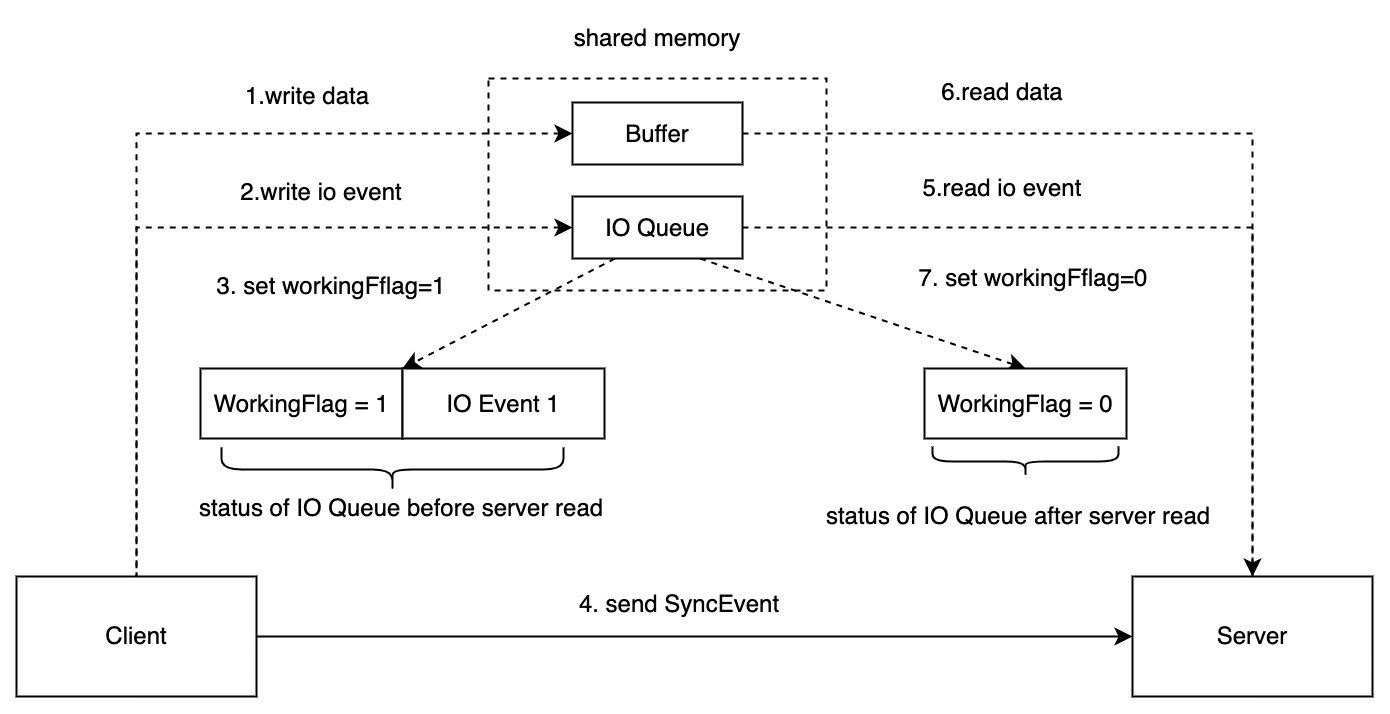

In online scenarios, real-time synchronization is required on demand for each data write, which requires a process synchronization operation (Step 4 in the figure below). Although the latency issue is resolved, to demonstrate the benefits of zero-copy on performance, the number of packets that require interaction needs to be greater than a relatively large threshold. Therefore, an IO queue was constructed in shared memory to complete batch IO operation, enabling benefits to be demonstrated even in small packet IO-intensive scenarios.

The core idea is that when a process writes a request to the IO queue, it notifies the other process to handle it. When the next request comes in(corresponding to IO Event 2~N in the figure, an IO Event can independently describe the position of a request in shared memory), if the other process is still processing requests in the IO queue, there is no need to send a notification. Therefore, the more dense the IO, the better the batching effect.

In addition, in offline scenarios, scheduled synchronization itself is a form of batch processing for IO, and the effect of batch processing can effectively reduce the system calls caused by process synchronization. The longer the sleep interval, the lower the overhead of process synchronization.

As for polling synchronization, there is no need to consider batch IO operation because this mechanism itself is designed to reduce process synchronization overhead. Polling synchronization directly occupies a CPU core, which is equivalent to defaulting to maximizing the synchronization mechanism overhead to achieve extremely low synchronization latency.

Performance

Benchmark

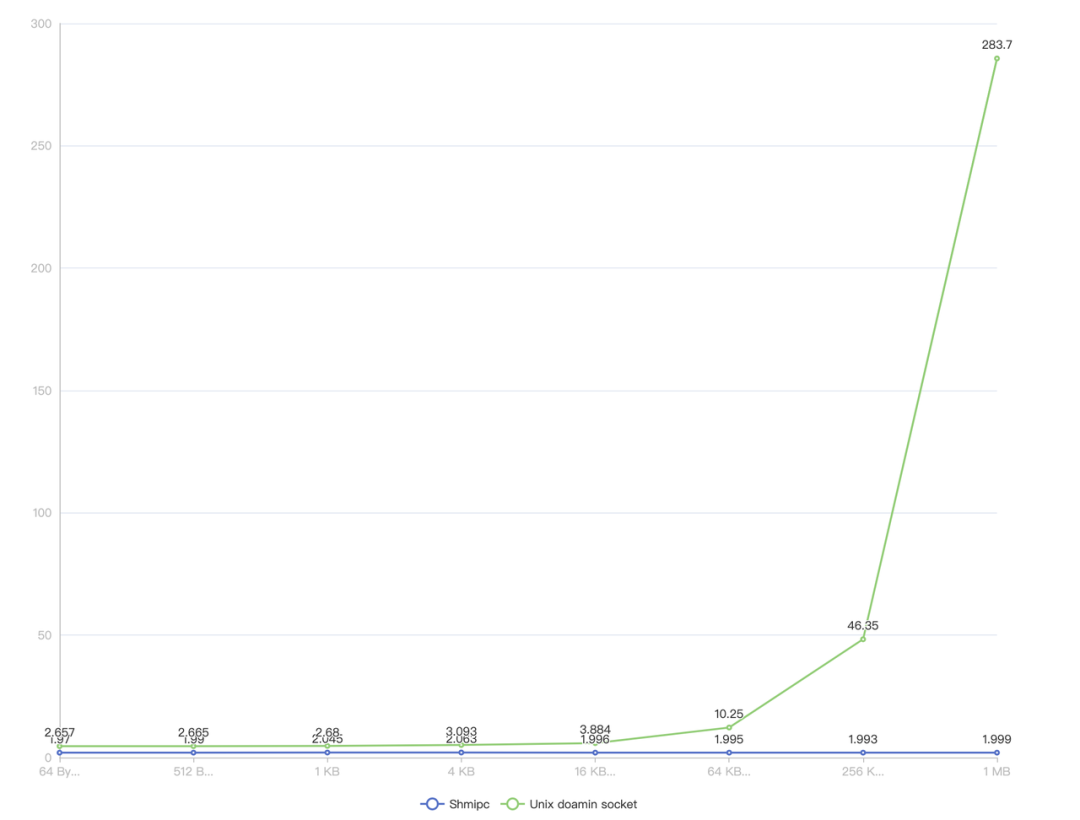

The X-axis represents the size of the data packet, and the Y-axis represents the time required for one Ping-Pong in microseconds, with smaller values being better. It can be seen that in small packet scenarios, Shmipc can also achieve some benefits compared to unix domain sockets, and performance improves as packet size increases.

Source: git clone https://github.com/cloudwego/shmipc-go && go test -bench=BenchmarkParallelPingPong -run BenchmarkParallelPingPong

Production Environment

In the Service Mesh ecosystem of ByteDance’s production environment, we have applied Shmipc in over 3,000 services and more than 1 million instances. Different business scenarios show different benefits, with the highest benefit being a 24% reduction in overall resource usage for the risk control business. Of course, there are also scenarios with no obvious benefits or even deterioration. However, significant benefits can be seen in both large packet and IO-intensive scenarios.

Lessons Learned

During the adoption process at ByteDance, we also encountered some pitfalls that caused some online accidents, which are quite valuable for reference.

- Shared memory leak. The shared memory allocation and recovery in the IPC process involve two processes and can easily lead to shared memory leaks if not careful.

Although the problem is very tricky, as long as it can be discovered actively when a leak occurs and there are observation methods to troubleshoot the leak afterwards, it can be solved.

- Active discovery. By increasing some statistics and summarizing them in the monitoring system, active discovery can be achieved, such as the total memory size allocated and recovered.

- Observation methods. When designing the layout of shared memory, adding some metadata enables us to analyze shared memory dumped by the built-in debug tool at the time of the leak, providing information on how much memory is leaked, what is in it, and some metadata related to this content.

- Packet congestion. Packet congestion is the most troublesome problem, which can cause serious consequences due to various reasons. We once had a packet congestion accident in a certain business, which was caused by the depletion of shared memory due to large packets. During the fallback to the normal path, there was a design defect, which caused a small probability of packet congestion. A valuable reference is to increase integration testing and unit testing in more scenarios to kill packet congestion in the cradle instead of explaining the investigation process and root cause.

- Shared memory trampling. ‘memfd’ should be used as much as possible to share memory, rather than the path of ‘mmap’ file system.

In the early days, the ‘mmap’ file system path was used for shared memory. The startup process of Shmipc and the path of shared memory were specified by environment variables,

and the boot process was injected into the application process. There is a situation where the application process may fork a process, which inherits the environment variables of the application process

and also integrates Shmipc. The forked process and the application process mmaped the same shared memory, resulting in trampling.

In ByteDance’s accident scenario, the application process used the golang plugin mechanism to load

.sofrom the outside to run, and the.sointegrated with Shmipc and ran in the application process. It could see all the environment variables, so it and the application process mmaped the same shared memory, resulting in undefined behavior during the operation. - Sigbus coredump. In the early days, shared memory is achieved through mmaping files under the

/dev/shm/path (tmpfs), and most application services were running in docker container instances. Container instances have capacity limits on tmpfs (which can be observed through df -h). This may cause a Sigbus error when the shared memory of mmap exceeds this limit. There will be no error reported by mmap itself, but the application process will crash when it accesses memory beyond the limit during runtime. To solve this problem, use ‘memfd’ to share memory, as in the third point.

RoadMap

- Integrate with the Golang RPC framework CloudWeGo/Kitex。

- Integrate with the Golang HTTP framework CloudWeGo/Hertz。

- Open-source Rust version of Shmipc and integrate with the Rust RPC framework CloudWeGo/Volo。

- Open-source C++ version of Shmipc.

- Introduce a timed synchronization mechanism for offline scenarios.

- Introduce a polling synchronization mechanism for scenarios with extreme latency requirements.

- Empower other IPC scenarios, such as IPC between Log SDK and Log Agent, IPC between Metrics SDK and Metrics Agent, etc.

Conclusion

We hope that this article can provide a basic understanding of Shmipc and its design principles. More implementation details and usage methods can be found in the projects of shmipc-spec and shmipc-go. Issues and PRs are always welcomed to the Shmipc project as well as the CloudWeGo community. We also hope that Shmipc can help more developers and enterprises build high-performance cloud-native architectures in the IPC field.