Performance Optimization on Kitex

Projects:

Preface

Kitex is the next generation high-performance and extensible Go RPC framework developed by ByteDance Service Framework Team. Compared with other RPC frameworks, in addition to its rich features for service governance, it has the following characteristics: integrated with the self-developed network library - Netpoll; supports multiple Message Protocols (Thrift, Protobuf) and Interactive Models (Ping-Pong, Oneway, Streaming); provides a more flexible and extensible code generator.

Currently, Kitex has been widely used by the major lines of business in ByteDance, and statistics shows that the number of service access is up to 8K. We’ve been continuously improving Kitex’s performance since its launch. This article will share our work on optimizing Netpoll and serialization.

Optimization of the Network Library - Netpoll

Netpoll, the self-developed network library based on Epoll. Compared with the previous version and the go net library, its performance has been significantly improved. Test results indicated that compared with the last version (2020.05), the latest version (2020.12) has ↑30% throughput capacity, ↓25% AVG latency, and ↓67% TP99 . Its performance is far better than the Go Net library. Below, we’ll share two solutions that can significantly improve its performance.

Optimizing Scheduling Delays When Calling “epoll_wait”

When Netpoll was newly released, it encountered the problem of low AVG latency but high TP99. Through our research and analysis on “epoll_wait”, we found that such a problem could be mitigated by integrating “polling” and “event trigger”. With such improvements in scheduling strategy, the latency can be reduced considerably.

Let’s have a look at the “syscall.EpollWait” method provided by Go first:

func EpollWait(epfd int, events []EpollEvent, msec int) (n int, err error)

Three parameters are provided here, they represent “epoll fd”, “callback events”, and “milliseconds to wait” respectively. Only “msec” is dynamic.

Normally, we would set “msec = -1” when we are actively calling “EpollWait”, as we want to wait for the event infinitely. In fact, many open-source net libraries were also using it in this way. But our research showed that setting “msec =-1” was not the optimal solution.

The kernel source (below) of “epoll_wait” shows that setting “msec = -1” arises extra “fetch_events” checks than setting “msec = 0”, and therefore consumes more time.

static int ep_poll(struct eventpoll *ep, struct epoll_event __user *events,

int maxevents, long timeout)

{

...

if (timeout > 0) {

...

} else if (timeout == 0) {

...

goto send_events;

}

fetch_events:

...

if (eavail)

goto send_events;

send_events:

...

The Benchmark shows that when an event is triggered, setting “msec = 0” is about 18% faster than setting “msec = -1”. Thus, when triggering complex events, setting “msec = 0” is obviously a better choice.

| Benchmark | time/op | bytes/op |

|---|---|---|

| BenchmarkEpollWait, msec=0 | 270 ns/op | 0 B/op |

| BenchmarkEpollWait, msec=-1 | 328 ns/op | 0 B/op |

| EpollWait Delta | -17.68% | ~ |

However, setting “msec = 0” would lead to infinite polling when no event is triggered, consumes lots of resources.

Taking the previously mentioned factors into account, it’s preferred to set “msec = 0” when an event is triggered and “msec = -1” when no event is triggered to reduce polling. The pseudocode is demonstrated as follows:

var msec = -1

for {

n, err = syscall.EpollWait(epfd, events, msec)

if n <= 0 {

msec = -1

continue

}

msec = 0

...

}

Nevertheless, our experiments have proved that the improvement is insignificant. Setting “msec = 0” merely reduces the delay of a single call by 50ns, which is not a considerable improvement. If we want to further reduce latency, adjustment must be made in Go runtime scheduling. Thus, let’s further explore this issue: In the pseudocode above, setting “msec= -1” with no triggered event, and “continue” directly will immediately execute “EpollWait” again. Since there is no triggered event while “msec = -1”, the current “goroutine” will block and be switched by “P” passively. However, it is less efficient, and we can save time if we actively switch “goroutine” for “P” before “continue”. So we modified the above pseudocode as follows:

var msec = -1

for {

n, err = syscall.EpollWait(epfd, events, msec)

if n <= 0 {

msec = -1

runtime.Gosched()

continue

}

msec = 0

...

}

The test results of the modified code showed that throughput ↑12% and TP99 ↓64%. The latency was significantly reduced.

Utilizing “unsafe.Pointer”

Through further study of “epoll_wait”, we find that the “syscall.EpollWait” published by Go and the “epollwait” used by “runtime” are two different versions, as they use different “EpollEvent”. They are demonstrated as follows:

// @syscall

type EpollEvent struct {

Events uint32

Fd int32

Pad int32

}

// @runtime

type epollevent struct {

events uint32

data [8]byte // unaligned uintptr

}

As we can see, the “epollevent” used by “runtime” is the original structure defined by “epoll” at system layer. The published version encapsulates it and splits “epoll_data(epollevent.data)” into two fixed fields: “Fd” and “Pad”. For “runtime”, in its source code we found the following logic:

*(**pollDesc)(unsafe.Pointer(&ev.data)) = pd

pd := *(**pollDesc)(unsafe.Pointer(&ev.data))

Obviously, “runtime” uses “epoll_data(&ev.data)” to store the pointer of the corresponding structure (pollDesc) of “fd” directly. Thus, when an event is triggered, the “struct” object can be found directly with the corresponding logic being executed. However, the external version can only obtain the encapsulated “fd” parameters. So it needs to introduce additional “Map” to manipulate the “struct” object, and the performance will be diminished.

Therefore, we abandoned “syscall.EpollWait” and designed our own “EpollWait” call by referring to “runtime”. We also use “unsafe.Pointer” to access “struct” objects. The test results showed that our “EpollWait” call contributed to ↑10% throughput and ↓10% TP99, which has significantly improved efficiency.

Serialization/Deserialization Optimization of Thrift

Serialization refers to the process of converting a data structure or object into a binary or textual form. Deserialization is the opposite process. A serialization protocol needs to be agreed during RPC communication. The serialization process is executed before the client sends requests. The bytes are transmitted to the server over the network, and the server will logic-process the bytes to complete an RPC request. Thrift supports “Binary”, “Compact”, and “JSON” serialization protocols. Since “Binary” is the most common protocol used in Bytedance, we will only discuss about “Binary” protocol.

“Binary” protocol is “TLV” (“Type”, “Length”, “Value”) encoded, that is, each field is described using “TLV” structure. It emphasizes that the “Value” can also be a “TLV” structure, where the “Type” and “Length” are fixed in length, and the length of “Value” is determined by the input value of “Length”. The TLV coding structure is simple, clear, and scalable. However, since it requires the input of “Type” and “Length”, there is extra memory overhead incurred. It wastes considerable memory especially when most fields are in base types.

The performance of serialization and deserialization can be optimized from two dimensions - “time” & “space”. To be compatible with the existing “binary” protocols, optimization in “space” seems to be infeasible. Improvement can only be made in “time”, it includes:

- Reduce the frequency of operations on memory, notably memory allocation and copying. Try to pre-allocate memory to reduce unnecessary time consumption.

- Reduce the frequency of function calls by adjusting code structure or using “inline” etc.

Research on Serialization Strategy

Based on “go_serialization_benchmarks”, we investigated a number of serialization schemes that performed well to guide the optimization of our serialization strategy.

Analysis of “protobuf”, “gogoprotobuf”, and “Cap ’n Proto” has provided us the following results:

- Considering I/O, the transmitted data is usually compressed in size during network transmission. “protobuf” uses “Varint” encoding and has good data compression capabilities in most scenarios.

- “gogoprotobuf” uses precomputation to reduce memory allocations and copies during serialization. Thus, it eliminates the cost of system calls, locks and GC arisen from memory allocations.

- “Cap ’n Proto” directly operates buffer, which also reduces memory allocations and copies. In addition, it also designs “struct pointer” in a way that processes fixed-length data and non-fixed-length data separately, which enables fast processing for fixed-length data.

For compatibility reasons, it is impossible to change the existing “TLV” encoding format, so data compression is not feasible. But finding 2 and 3 are inspiring to our optimization work, and in fact we have taken a similar approach.

Approaches

Reducing Operations on Memory

Buffer management

Both serialization and deserialization involve copying data from one piece of memory to another. It involves memory allocation and memory copying. Avoiding memory operations can reduce unnecessary overhead such as system calls, locks, and GC.

In fact, Kitex has provided “LinkBuffer” for buffer management purposes. “LinkBuffer” is designed with a linked structure and consists of multiple blocks, among which blocks are memory chunks with a fixed size. Object pool is constructed to maintain unoccupied block and support block multiplexing, thus, reduce memory usage and GC.

Initially we simply used “sync.Pool” to multiplex the “LinkBufferNode” of netpoll, but it didn’t significantly contribute to multiplexing in large data package scenarios (large nodes can’t be reclaimed or it would cause memory leaking). At present, we have changed our strategy to maintain a group of “sync.Pool”, and the buffer size in each chunk is different. When new blocks are created, it is obtained from the pool with the closest size to the required size, so that the memory can be multiplexed as much as possible. And the test results also proved that it contributed to significant improvement in terms of memory allocation and GC.

Copy-free String / Binary

For some services, such as video-related services, during its request or return processes, large-size “Binary” data will be arisen, representing the processed video or image data. Meanwhile, some services will return large-size “String” data (such as full-text information, etc.). In this scenario, all the hot spots we see through the flame graph are on the copies of the data. So we thought, can we reduce the frequency of such copies?

The answer is positive. Since our underlying buffer is a linked list, it is easy to insert a node in the middle of the list.

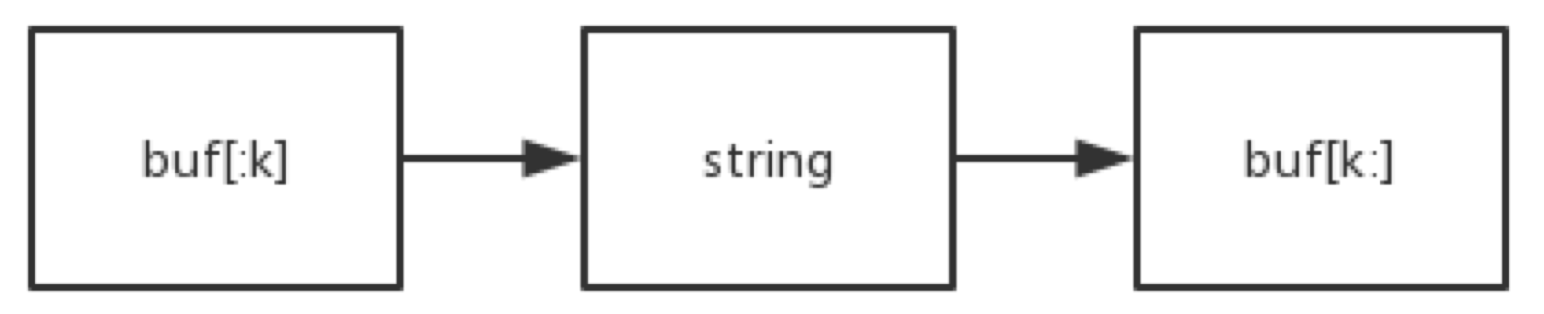

Thus, we have taken a similar approach, when a “string” or “binary” data exists during serialization processes. First, split the node’s buffer into two segments and then insert the buffer of the “string” / “binary” objects in the middle correspondingly. This avoids the copy of large “string” / “binary” .

Furthermore, a copy will occur if we convert a string to “[]byte” using “[]byte(string)”. Because “string” is immutable and “[]byte” is mutable in Golang language. “unsafe” is needed if you don’t want to copy during the conversion:

func StringToSliceByte(s string) []byte {

l := len(s)

return *(*[]byte)(unsafe.Pointer(&reflect.SliceHeader{

Data: (*(*reflect.StringHeader)(unsafe.Pointer(&s))).Data,

Len: l,

Cap: l,

}))

}

The meaning of this demonstrated code is to take the address of the string first, and then give it a slice byte header, so that the “string” can be converted into “[]byte” without copying the data. Note that the resulting “[]byte” is not writable, or the behavior is undefined.

Pre-Calculation

Some services support transmissions of large data package, which incurs considerable serialization / deserialization overhead. Generally, large packages are associated with the large size of the container type. If the buffer can be pre-calculated, some O(n) operations can be reduced to O(1), and further reduce the frequency of function calls. In the case of large data packages, the number of memory allocation can also be greatly reduced, bringing considerable benefits.

Base types

- If the container element is defined as base type (bool, byte, i16, i32, i64, double), the total size can be pre-calculated during serialization as its size is fixed, and enough buffer can be allocated at once. The number of “malloc” operations of O(n) can be reduced to O(1), thus greatly reducing the frequency of “malloc” operations. Similarly, the number of “next” operations can be reduced during deserialization.

Rearrangement of “Struct” Fields

- The above optimizations are valid only for container elements that are defined as base types. Can they be optimized for “struct” elements? The answer is yes.

- If there are fields of base type in “struct”, we can pre-calculate the size of these fields, then allocate buffer for these fields in advance during serialization and write these fields in the first order. We can also reduce the frequency of “malloc”.

Size calculation

- The optimization mentioned above is for base types. If you first iterate over all the fields of the request during serialization, you can calculate the size of the entire request, allocate buffer in advance, and directly manipulate buffer during serialization and deserialization, so that the optimization effect can be achieved for non-base types.

- Define a new “codec” interface:

type thriftMsgFastCodec interface {

BLength() int // count length of whole req/resp

FastWrite(buf []byte) int

FastRead(buf []byte) (int, error)

}

- Change the “Marshal” and “Unmarshal” interfaces accordingly:

func (c thriftCodec) Marshal(ctx context.Context, message remote.Message, out remote.ByteBuffer) error {

...

if msg, ok := data.(thriftMsgFastCodec); ok {

msgBeginLen := bthrift.Binary.MessageBeginLength(methodName, thrift.TMessageType(msgType), int32(seqID))

msgEndLen := bthrift.Binary.MessageEndLength()

buf, err := out.Malloc(msgBeginLen + msg.BLength() + msgEndLen)// malloc once

if err != nil {

return perrors.NewProtocolErrorWithMsg(fmt.Sprintf("thrift marshal, Malloc failed: %s", err.Error()))

}

offset := bthrift.Binary.WriteMessageBegin(buf, methodName, thrift.TMessageType(msgType), int32(seqID))

offset += msg.FastWrite(buf[offset:])

bthrift.Binary.WriteMessageEnd(buf[offset:])

return nil

}

...

}

func (c thriftCodec) Unmarshal(ctx context.Context, message remote.Message, in remote.ByteBuffer) error {

...

data := message.Data()

if msg, ok := data.(thriftMsgFastCodec); ok && message.PayloadLen() != 0 {

msgBeginLen := bthrift.Binary.MessageBeginLength(methodName, msgType, seqID)

buf, err := tProt.next(message.PayloadLen() - msgBeginLen - bthrift.Binary.MessageEndLength()) // next once

if err != nil {

return remote.NewTransError(remote.PROTOCOL_ERROR, err.Error())

}

_, err = msg.FastRead(buf)

if err != nil {

return remote.NewTransError(remote.PROTOCOL_ERROR, err.Error())

}

err = tProt.ReadMessageEnd()

if err != nil {

return remote.NewTransError(remote.PROTOCOL_ERROR, err.Error())

}

tProt.Recycle()

return err

}

...

}

- Modify the generated code accordingly:

func (p *Demo) BLength() int {

l := 0

l += bthrift.Binary.StructBeginLength("Demo")

if p != nil {

l += p.field1Length()

l += p.field2Length()

l += p.field3Length()

...

}

l += bthrift.Binary.FieldStopLength()

l += bthrift.Binary.StructEndLength()

return l

}

func (p *Demo) FastWrite(buf []byte) int {

offset := 0

offset += bthrift.Binary.WriteStructBegin(buf[offset:], "Demo")

if p != nil {

offset += p.fastWriteField2(buf[offset:])

offset += p.fastWriteField4(buf[offset:])

offset += p.fastWriteField1(buf[offset:])

offset += p.fastWriteField3(buf[offset:])

}

offset += bthrift.Binary.WriteFieldStop(buf[offset:])

offset += bthrift.Binary.WriteStructEnd(buf[offset:])

return offset

}

Optimizing Thrift Encoding with SIMD

“list<i64/i32>” is widely used in the company to carry the ID list, and the encoding method of “list<i64/i32>” is highly consistent with the rule of vectorization. Thus, we use SIMD to optimize the encoding process of list<i64/i32>.

We implement “avx2” to improve the encoding process, and the improved results are significant. When dealing with large amounts of data, the performance can be improved by 6 times for i64 and 12 times for i32. In the case of small data volume, the improvement is more obvious, which achieves 10 times for i64 and 20 times for I32.

Reducing Function Calls

inline

The purpose of “inline” is to expand a function call during its compilation and replace it with the implementation of the function. It improves program performance by reducing the overhead of the function call.

“inline” can’t be implemented on all functions in Go. Run the process with the argument - (gflags="-m") to display the functions that are inlined. The following conditions cannot be inlined:

- A function containing a loop;

- Functions that include: closure calls, select, for, defer, coroutines created by the go keyword;

- For Functions over a certain length, by default when parsing the AST, Go applies 80 nodes. Each node consumes one unit of inline budget. For example, a = a + 1 contains five nodes: AS, NAME, ADD, NAME, LITERAL. When the overhead of a function exceeds this budget, it cannot be inlined.

You can specify the intensity (go 1.9+) of the compiler’s inlined code by specifying “-l” at compile time. But it is not recommended, as in our test scenario, it is buggy and does not work:

// The debug['l'] flag controls the aggressiveness. Note that main() swaps level 0 and 1, making 1 the default and -l disable. Additional levels (beyond -l) may be buggy and are not supported.

// 0: disabled

// 1: 80-nodes leaf functions, oneliners, panic, lazy typechecking (default)

// 2: (unassigned)

// 3: (unassigned)

// 4: allow non-leaf functions

Although using “inline” can reduce the overhead of function calls, it may also lead to lower CPU cache hit rate due to code redundancy. Therefore, excessive usage of “inline” should not be blindly pursued, and specific analysis should be carried out based on “profile” results.

go test -gcflags='-m=2' -v -test.run TestNewCodec 2>&1 | grep "function too complex" | wc -l

48

go test -gcflags='-m=2 -l=4' -v -test.run TestNewCodec 2>&1 | grep "function too complex" | wc -l

25

As you can see, from the output above, increasing the inline intensity does reduce the “function too complex”. Following are the benchmark results:

| Benchmark | time/op | bytes/op | allocs/op |

|---|---|---|---|

| BenchmarkOldMarshal-4 | 309 µs ± 2% | 218KB | 11 |

| BenchmarkNewMarshal-4 | 310 µs ± 3% | 218KB | 11 |

It reveals that turning on the highest level of inlining intensity does eliminate many functions that cannot be inlined due to “function too complex”, but the test results show that the improvement is insignificant.

Testing Results

We built benchmarks to compare performance before and after optimization, and here are the results. Testing Environment: Go 1.13.5 darwin/amd64 on a 2.5 GHz Intel Core i7 16GB

Small Data Size

Data size: 20KB

| Benchmark | time/op | bytes/op | allocs/op |

|---|---|---|---|

| BenchmarkOldMarshal-4 | 138 µs ± 3% | 25.4KB | 19 |

| BenchmarkNewMarshal-4 | 29 µs ± 3% | 26.4KB | 11 |

| Marshal Delta | -78.97% | 3.87% | -42.11% |

| BenchmarkOldUnmarshal-4 | 199 µs ± 3% | 4720 | 1360 |

| BenchmarkNewUnmarshal-4 | 94µs ± 5% | 4700 | 1280 |

| Unmarshal Delta | -52.93% | -0.24% | -5.38% |

Large Data Size

Data size: 6MB

| Benchmark | time/op | bytes/op | allocs/op |

|---|---|---|---|

| BenchmarkOldMarshal-4 | 58.7ms ± 5% | 6.96MB | 3350 |

| BenchmarkNewMarshal-4 | 13.3ms ± 3% | 6.84MB | 10 |

| Marshal Delta | -77.30% | -1.71% | -99.64% |

| BenchmarkOldUnmarshal-4 | 56.6ms ± 3% | 17.4MB | 391000 |

| BenchmarkNewUnmarshal-4 | 26.8ms ± 5% | 17.5MB | 390000 |

| Unmarshal Delta | -52.54% | 0.09% | -0.37% |

Copy-free Serialization

In some services with large request and response data, the cost of serialization and deserialization is high. There are two ways for optimization:

- Implement the optimization strategy on serialization and deserialization as described earlier.

- Scheduling by copy-free serialization.

Research on Copy-free Serilization

RPC through copy-free serialization, which originated from the “Cap ’n Proto” project of Kenton Varda. “Cap ’n Proto” provides a set of data exchange formats and corresponding codec libraries.

In essence, “Cap ’n Proto” creates a bytes slice as buffer, and all read & write operations on data structures are directly operated on buffer. After reading & writing, information contained by the buffer is added to the head and can be sent directly. And the peer end can read it after receiving it. Since there is no Go structure as an intermediate storage, serialization and deserialization are not required.

To briefly summarize the characteristics of “Cap ’n Proto”:

- All data is read and written to a contiguous memory.

- The serialization operation is preceded. “Get/Set” data and encoding process in parallel.

- In the data exchange format, pointer (“offset” at the data memory) mechanism is used to store data at any location in the contiguous memory, so that data in the structure can be read and written in any order.

- Fixed-size fields of a structure are rearranged so that they are stored in contiguous memory.

- Fields with indeterminate size of a structure (e.g. list), are represented by a fixed-size pointer that stores information including the location of the data.

First of all, “Cap ’n Proto” has no Go language structure as an intermediate carrier, which can reduce a copy. Then, “Cap ’n Proto” operates on a contiguous memory, and the read and write of coded data can be completed at once. Because of these two reasons, Cap ’n Proto has excellent performance.

Here are the benchmarks of “Thrift” and “Cap ’n Proto” for the same data structure. Considering that “Cap ’n Proto” presets the codec operation, we compare the complete process including data initialization. That is, structure data initialization + (serialization) + write buffer + read from buffer + (deserialization) + read from structure.

struct MyTest {

1: i64 Num,

2: Ano Ano,

3: list<i64> Nums, // 长度131072 大小1MB

}

struct Ano {

1: i64 Num,

}

| Benchmark | Iter | time/op | bytes/op | alloc/op |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BenchmarkThriftReadWrite | 172 | 6855840 ns/op | 3154209 B/op | 545 allocs/op |

| BenchmarkCapnpReadWrite | 1500 | 844924 ns/op | 2085713 B/op | 9 allocs/op |

| ReadWrite Delta | / | -87.68% | -33.88% | -98.35% |

(deserialization) + read data, depending on the size of data package,“Cap ’n Proto” performance is about 8-9 times better than “Thrift”. Write data + (serialization), depending on the size of data package, “Cap ’n Proto” performance is approximately 2-8 times better than “Thrift”. Overall performance of “Cap ’n Proto” is approximately 4-8 times better than “Thrift”.

Previously, we discussed the advantages of “Cap ’n Proto”. We will then summarize some problems existing in “Cap ’n Proto”:

- One problem with the contiguous memory of Cap ’n Proto is that when the data of variable size is resized, and the required space is larger than the original space, the space of the original data can only be reallocated later. As a result, the original space becomes a hole that cannot be removed. This problem gets worse as the call link is resized, and can only be solved with strict constraints throughout the link: avoid resizing variable size fields, and when resize is necessary, rebuild a structure and make a deep copy of the data.

- “Cap ’n Proto” has no Go language structure as an intermediate carrier, so all fields can only be read and written through the interface, resulting in poor user experience.

Thrift Protocol‘s Compatible Copy-free Serialization

In order to support copy-free serialization better and more efficiently, “Cap ’n Proto” uses a self-developed codec format, but it is difficult to be implemented in the current environment where “Thrift” and “ProtoBuf” are dominant. In order to achieve the performance of copy-free serialization with protocol compatibility, we started the exploration of copy-free serialization that is compatible with “Thrift” protocol.

“Cap ’n Proto” is a benchmark for copy-free serialization, so let’s see if the optimizations on “Cap ’n Proto” can be applied to Thrift:

- Nature is the core of copy-free serialization, which does not use Go structure as intermediate carriers to reduce one copy. This optimization is not about a particular protocol and can be applied to any existing protocol (So it’s naturally compatible with the Thrift protocol), but the user experience of “Cap ’n Proto” reflects that it needs to be carefully polished.

- “Cap ’n Proto” is operated on a contiguous memory. The read & write of the encoded data can be completed at once. “Cap ’n Proto” can operate on contiguous memory because there is a pointer mechanism that allows data to be stored anywhere, allowing fields to be written in any order without affecting decoding. However, it is very likely to leave a hole in the resize due to misoperation on contiguous memory. Besides, “Thrift” has no pointer alike mechanism, so it has stricter requirements on data layout. Here are two ways to approach such problems:

- Insist on operating in contiguous memory, while imposing strict regulations on users’ usage: 1. Resize operation must rebuild the data structure; 2. When a structure is nested, there are strict requirements on the order in which the fields are written (we can think of it as unfolding a nested structure from the outside in, and being written in the same order) . In addition, due to TLV encoding such as Binary, when writing begins for each nesting, it requires declaration (such as “StartWriteFieldX”).

- Operating not entirely in contiguous memory, alterable fields are allocated a separate piece of memory. Since memory is not completely contiguous, the write operation can’t complete the output at once. In order to get closer to the performance of writing data at once, we adopted a linked buffer scheme. On the one hand, when the variable field resize occurs, only one node of the linked buffer is replaced, and there is no need to reconstruct the structure like “Cap ’n Proto”. On the other hand, there is no need to clarify the actual structure like “Thrift” when the output is needed, just write the buffer on the link.

To summarize what we have determined previously: 1. Do not use Go structure as the intermediate carrier, directly operate the underlying memory through the interface, and complete the codec at the same time of “Get/Set”. 2. Data is stored through a linked buffer.

Then let’s take a look at the remaining issues:

- Degradation of the user experience caused by not using Go structures.

- Solution: Improve the user experience of “Get/Set” interface and make it as easy to use as the Go structure.

- Binary Format of “Cap ’n Proto” is designed specifically for copy-free serialization scenarios, and although decoding is performed once for every Get, the decoding costs are minimal. The “Thrift” protocol (taking “Binary” as an example) has no mechanism that is similar to pointer. When there are multiple fields of variable size or nesting, they must be resolved sequentially instead of directly calculating the offset to get the field data location. Moreover, the cost of sequential resolution for each Get is too high.

- Solution: In addition to recording the structure’s buffer nodes, we also add an index that records the pointer to the buffer node at the beginning of each field with unfixed size. The following is the ultimate performance comparison test between the current copy-free serialization scheme and “FastRead/Write” under the condition of 4 cores:

| Package Size | Type | QPS | TP90 | TP99 | TP999 | CPU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1KB | Non-serialization | 70,700 | 1 ms | 3 ms | 6 ms | / |

| FastWrite/FastRead | 82,490 | 1 ms | 2 ms | 4 ms | / | |

| 2KB | Non-serialization | 65,000 | 1 ms | 4 ms | 9 ms | / |

| FastWrite/FastRead | 72,000 | 1 ms | 2 ms | 8 ms | / | |

| 4KB | Non-serialization | 56,400 | 2 ms | 5 ms | 10 ms | 380% |

| FastWrite/FastRead | 52,700 | 2 ms | 4 ms | 10 ms | 380% | |

| 32KB | Non-serialization | 27,400 | / | / | / | / |

| FastWrite/FastRead | 19,500 | / | / | / | / | |

| 1MB | Non-serialization | 986 | 53 ms | 56 ms | 59 ms | 260% |

| FastWrite/FastRead | 942 | 55 ms | 59 ms | 62 ms | 290% | |

| 10MB | Non-serialization | 82 | 630 ms | 640 ms | 645 ms | 240% |

| FastWrite/FastRead | 82 | 630 ms | 640 ms | 640 ms | 270 |

Summary of the test results:

- In small data package scenario, performance of non-serialization is poorer - about 85% of FastWrite/FastRead’s performance.

- In large data package scenario, the performance of non-serialization is better. When processing packages larger than 4K, the performance of non-serialization is 7%-40% better compared with “FastWrite/FastRead”.

Postscript

Hope the above sharing can be helpful to the community. At the same time, we are trying to share memory-based IPC, io_uring, TCP zero copy, RDMA, etc., to better improve Kitex performance. And we will also focus on improving the communication scenarios of the same device and container. Welcome to join us and contribute to Go ecology together!